Are You An "Abundant" Elected Official?

An open call to the protagonists of the Abundance Movement.

Recently we published a post defining Abundance: it’s an emerging political ideology and identity—“I’m an ‘Abundant’”—for people fighting today’s system-level villains—narrow interest capture and state incapacity—to improve outcomes for regular people.

While there are many actors in the drama of politics and policy making—e.g. advocates, donors, journalists, academics, government staff, and voters themselves—the protagonists are elected officials.

So if you’re an elected official reading our posts, how would you know you’re an “Abundant?”

In this piece, we’ll move beyond the “I know it when I see it” definition of an elected Abundant to something more concrete.

Abundant Electeds Are Anti-Capture

Let’s start by making an important observation: it’s definitionally hard to be an anti-capture elected. Why? Because per our previous post:

“Capture” means a policy process is overly responsive to a narrow (unrepresentative) slice of the electorate.

The unrepresentative slice is the one showing up! They are donating money to campaigns and running independent expenditures against candidates who oppose their priorities. They employ lobbyists to present their point of view in the best available light. They make their voices heard during public comment. They are the superusers of the system.

Who are these influential interests? It depends on where you are, but in cities it tends to be groups like police, fire, and teachers’ unions, chambers of commerce, realtors, and a subset of local homeowners. None of these groups are inherently bad. They have a valid point of view and voice in discussions that affect their interests. The problem is we over-index on their needs because they show up and participate and the rest of us don’t.

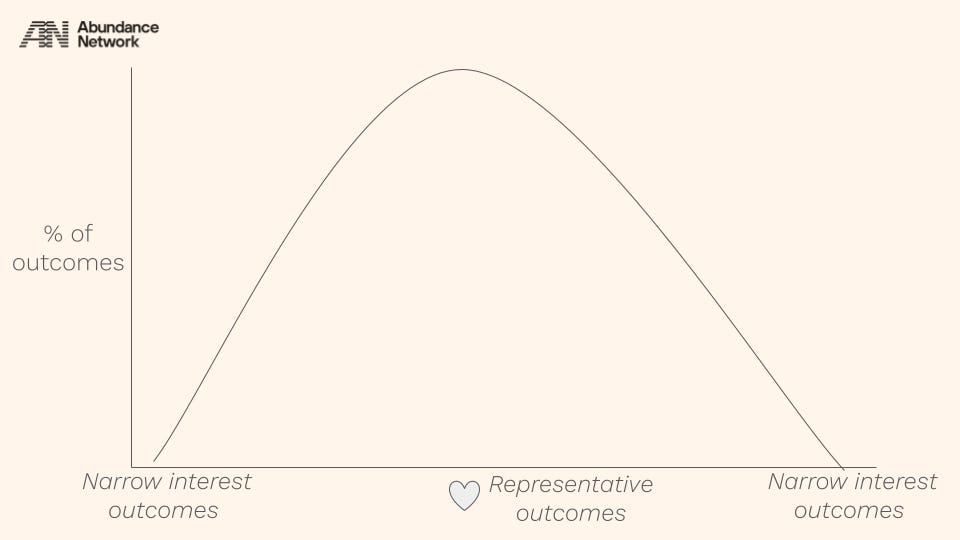

In an ideal world, the interests on various sides of an issue are equally powered and end up arriving at a “representative” view on the topic, and the resulting policy approaches a “representative outcome.”

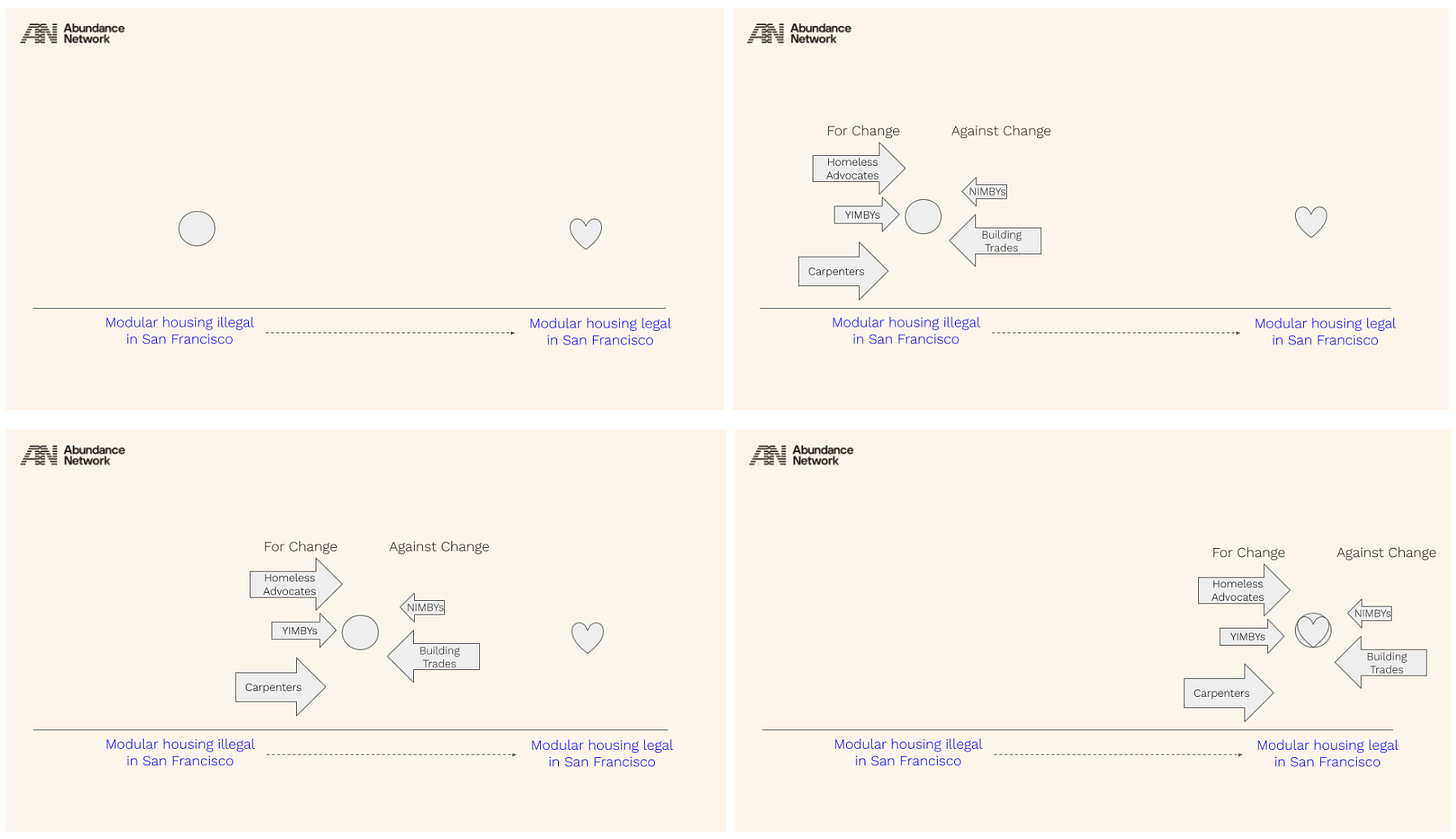

Here’s an (oversimplified) example of what it might look like on a particular policy issue in a particular geography:1

In real life, many policy areas don’t have well-balanced interests and we end up with a status quo far away from a representative outcome.

So how do you know you’re an anti-capture elected?

First, you’d have a record of votes that match your conception of the public good,2 but are against the preferences of the traditional superuser interest groups. Exactly what that looks like depends on the politics of your jurisdiction, but it might include things like:

Accelerating the timeline to school reopening against the preference of teachers’ unions.

Streamlining housing permit approvals against the preferences of the Building Trades and a subset of homeowners.

Allowing nurse practitioners to practice to the “top of their license” against the preferences of the doctors’ associations who want to guard their members’ interests. (a form of professional NIMBYism)

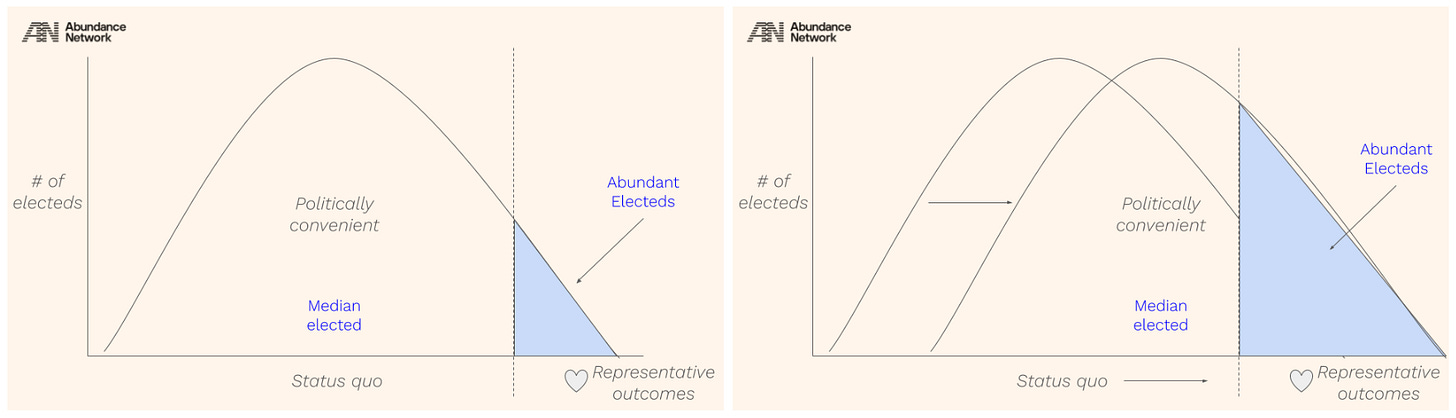

So if you are an Abundant on the dimension of anti-capture, you’re a relative outlier among your peers, taking politically inconvenient votes on issues that move toward representative outcomes.

Abundant Electeds Want More State Capacity

The second core pillar of Abundance is the fight for more state capacity. The Niskanen Center has a good primer on state capacity. (60 min) The baptismal experience to understand state capacity in your bones is reading Jen Pahlka’s Recoding America. Our book summary is here. (20 min)

Before we jump into the behaviors of a state capacity elected,3 let’s first spend a moment on the problem.

We elect people to represent us. Each year they do a lot of activity: press releases, committee hearings, bill introductions, community events, etc. Collectively they add many new laws to the books. And yet outcomes don’t seem to improve.

What’s wrong? Certainly part of it is that the laws they’re passing are most responsive to the most aggressively organized interests, per the capture story above. But even when we have policy intentions that approximate the representative will, we struggle to implement them.

We think that fundamentally comes down to the working relationship between the legislative and executive branches. By our constitutional set up, the legislative branch writes laws and the executive branch implements them. But the working conditions in today’s executive branch are not conducive to implementation, and the legislative branch spends relatively little time and attention working to improve these conditions.

The words legislators write don’t magically fix problems. They are a set of instructions, whether high level or detailed, that need to be carried out by the humans who work in the executive branch of government (e.g. people who work in departments like public works, police, fire, or economic development). Moreover, these instructions are almost always additive to previous instructions, and the authors rarely understand how the new ones interact with the old ones, often with an unintentional “everything bagel” effect.

So how does a state capacity elected in a legislative role act in a way that’s different from the typical elected official? Fundamentally they spend a lot more time thinking about the way the laws4 they write will be implemented.5 They think of their “customer” as not just their end constituent/voter who is relying on government to work, but also the government staffer who will be on the receiving end of their law and is responsible for transmuting the lawmaker’s policy into the constituents’ reality.

Some characteristics of the way a state capacity lawmaker approaches their job:

They spend less time writing new bills and more time conducting oversight—where oversight means curiosity and support, not gotcha—of past bills to learn what’s working and not working.

They build relationships and have dialogue6 with all of the downstream “customers” of their laws, including not just constituents but also relevant departments or subsidiary jurisdictions.

They assume there will be unintended consequences to their work, and that a first bill will require “clean up” legislation in future years. And they build the trust needed to get the information needed to do that clean up well.

They look not just to add new provisions and requirements into a policy domain, but also subtract them.

They concern themselves with the foundational conditions in which departments do their work, including rules around hiring, procurement, funding, technology, etc.

Whereas courage might be the key trait of an anti-capture elected—standing up to narrow interests for the benefit of a broader (more disengaged) public—the key traits of a state capacity elected are being humble and outcome-oriented.

Humble because it takes recognizing we live in a complex world where our initial solutions to social problems are only best guesses.7 A legislator’s magic words, even spoken with democratic legitimacy behind them, don’t automagically become reality without government staff implementing them.

And outcome-oriented because it is easier to write a press release than it is to doggedly follow through on the results of a well-intentioned bill, especially when feedback loops are long and media, advocate, donor, and voter attention spans are short.

So our visual of a state capacity lawmaker looks similar to the anti-capture lawmaker:

Conclusion and Next Steps

We define Abundance as the fight against capture and state incapacity to increase the availability of the building blocks of a good life—e.g. housing, transportation, energy, education, safety, and healthcare.

So what does it look like to be an Abundant elected official? An Abundant elected takes hard votes8 and does the hard work of improving real-world outcomes, focusing not just on bills and constituents but also on the working conditions within departments, where the people who implement their ideas live.

We have a small readership here at Modern Power—no more than a few thousand people will read this post. But it’s our hope and belief that among our readers, there will be a handful of elected officials who see themselves in this post. They will say, “I am an Abundant.”

Then we hope they (you!) reach out to us. Because our goal with the Abundance Movement is to shift the interest group bell curve such that politically convenient votes and activities move closer to the representative ideal.

The YIMBY movement, the best example of on-the-ground Abundance, provides a guide for our efforts.

In the early days, it was politically convenient to oppose housing. Then the combination of a few YIMBY elected champions taking politically hard votes (e.g. Nancy Skinner, Scott Wiener) + advocates educating and organizing donors, voters, and the media led to a shift in the landscape of political convenience. This has significantly grown the number of electeds taking pro-housing votes over the past five years.

We aim to replicate this across additional issue areas with high capture and low state capacity in the coming years, thus creating the conditions for the emergence of more Abundant electeds. And if we had more Abundant electeds—at the risk of mixing bell curve metaphors—we’d end up with a distribution of public policy outcomes that looks more like what we would want and expect.

We are early in this story. You are our protagonist. Help us build a movement that supports you in supporting the public good. Email us: giselle@abundancenetwork.com.

Thanks to all the folks who shaped this piece, from inspiration to line editing: David Chiu, Giselle Hale, Jen Pahlka, Mike Greenfield, Nancy Skinner, Phil Levin, and Scott Wiener.

Reality is more complicated. Modular housing is still not the norm in San Francisco, despite at least one shining example of its potential promise. That’s partially a function of the size of the arrows of the pro and anti-change advocates (e.g. the Building Trades are a powerful union in San Francisco), and partially because, given the overall structure of our politics, it’s a lot easier to defend the status quo than to change it.

Arriving at a conception of the public good, or the representative will, is more art than science. What we see in the Abundant electeds we know is they avoid overweighting the opinions of the superusers of the system. But the exact mechanics of this will hopefully be the subject of a future Modern Power post.

Here it’s worth making a distinction among electeds. Most elected positions are in the legislative branch (e.g. city councils, state legislatures, Congress). There are also a handful of elected positions in the executive branch (e.g. Mayors, Governors, the President). Since the vast majority of elected officials are in legislative positions, and since we believe our state capacity issues stem principally from the disjunct between the legislative and executive branches, we’ve written this piece from the point of view of a legislative elected official.

Or motions or ordinances or whatever legal vehicle is relevant at the appropriate level of government.

And the conditions under which it will be implemented, and the incentives of those implementers.

“Dialogue” here is used literally. This is a two-way conversation, in contrast to one-way directives. A state capacity legislator actually listens, often changing their own behavior in response to their inquiries, not just punishing or rewarding folks downstream of their laws.

Per Tom Loosemore, cofounder of the UK Government Digital Service, “Why is most policy educated guesswork with a feedback loop measured in years?”

We recognize electeds sometimes have to strategically do the wrong thing in order to keep their seats, such that they can do the right thing when it matters more. (e.g. LBJ on civil rights) But there’s a difference between strategic votes that position an elected for impact and being captured by a narrow interest. Admittedly it can be hard to see and distinguish between two identical surface-level behaviors!

Dear Misha and company—

I am excited about the Abundance movement. It's really important, and I want it to succeed. Please take the following comment in that spirit.

> First, you’d have a record of votes that match your conception of the public good, but are against the preferences of the traditional superuser interest groups.

You are making a fatal mistake here: confusing the politics of the status quo and rentiers with politics-as-such. Politics-as-such runs by transactional negotiations among concentrated interests, not by above-the-fray "good policy" types transcending parochial concerns.

> the combination of a few YIMBY elected champions taking politically hard votes (e.g. Nancy Skinner, Scott Wiener)

You're reading history backwards. Scott didn't hurt his career by becoming pro-housing; he accelerated it. The bad guys aren't political and the good guys aren't above politics. It's all politics. YIMBY has made progress by doing transactional politics. Consider Scott's reaction to the defeat of ambitious bills: he works with interest groups and other legislators to determine what will shift their votes, and makes the changes necessary to get a good bill passed where a great one failed.

Abundance can do an enormous amount of good. I plan to support it. But it will succeed only if it is a political movement that grapples with how politics works, not if it is an attempt to be more pure than politics.

With respect this reads like a movement written in corporate speak. I’ve read Bertrand Russell and Wittgenstein and this article was more dense than either.

I don’t think you’re going to get many “Abundance” politicians in a democracy with elections taking place every 2 years and campaign finance the way it is