The challenges of the 21st century demand a more muscular, competent government than we’ve had in the US over the past few decades. Climate change, democratic backsliding, rising China, artificial intelligence and biotechnology risk, etc. are hard problems to solve. With a government in retreat, we will not succeed. In order to transform government over the next decade or two, we need a new aspirational politics that transcends petty partisan bickering.

“Abundance” can be the container for that politics: it’s more of the good stuff, broadly available and affordable to regular people. It’s abundant housing, clean energy, education, public safety, dignified jobs, etc. It adds up to abundant opportunity, so zip code doesn’t determine life outcome, and your kids’ life prospects are better than your own.

To achieve Abundance, we need to nail both policy & implementation, but to date we’ve mainly thought of Abundance as the outcomes we want + the policies we need to get there. This ignores implementation.1

The ability for government to accomplish its policy objectives is called “State Capacity.”

Abundance needs State Capacity, and State Capacity needs Abundance.

Why Abundance Needs State Capacity

Derek Thompson’s original Abundance Agenda essay (25 min) references 9 issue areas, with two pathways for driving outcomes: supply-side reforms, and industrial policy.

There are two ways in which this agenda is incomplete and needs State Capacity as a complement:

In the given issue areas, it’s not just supply-side reforms or industrial policy that will lead to great outcomes, but also state capacity

To build a “whole politics” — one that speaks to the varied needs of the citizenry — there are a bunch of other important issues (e.g. public safety, homelessness) that don’t have supply-side or industrial policy answers, and where state capacity is key to achieving abundant outcomes.

Take housing as an example. We’ve made progress building political will for supply-side reforms (e.g. ADU, duplexes) which is a big piece of the puzzle. At the same time we’ve cleverly routed around some of the state capacity issues by taking housing types not only out of the political decision-making veto flow (which is the supply-side constraint) but also out of certain bureaucratic vortexes like CEQA review, which, because of limited state capacity, becomes a huge time drag.

These reforms should help us break out of the flatline housing production we’ve had over the past 5 years.

But to fully realize the vision of Abundant housing, we have to do improve the machinery of government operations — how long does it take to issue a building permit; is there effective enforcement when cities don’t follow state law; are we able to build low-income and supportive housing at reasonable costs for the segment of our population that market solutions will never solve for?

Then take public safety as a missing issue in Derek’s framework but which we need for a “whole politics” that speaks to the full range of voters needs. There is not a “supply-side” or “industrial policy” solution to this issue. Public safety outcomes are the result of interactions among a set of systems — e.g. housing, education, mental health, welfare, gun laws, the criminal justice system, etc.

To improve public safety, we need to improve state capacity. We need better training & standards for police departments. We need more experimentation with diversion programs. We need better data to understand interactions between the systems listed above.

The more human the system, the more intersecting pieces, the more we need government structures oriented around learning and continuous improvement. That’s modern state capacity.

Why State Capacity Needs Abundance

Hard problems are hard. In advocating for more state capacity, we’re really saying we need to reimagine how government operates in the 21st century. This problem statement runs the risk of boiling the ocean. 35% of GDP is spent on government — it’s a multi-trillion dollar system. It’s also a fractured system. Government is not one entity. There are 90,000 governments in the US.

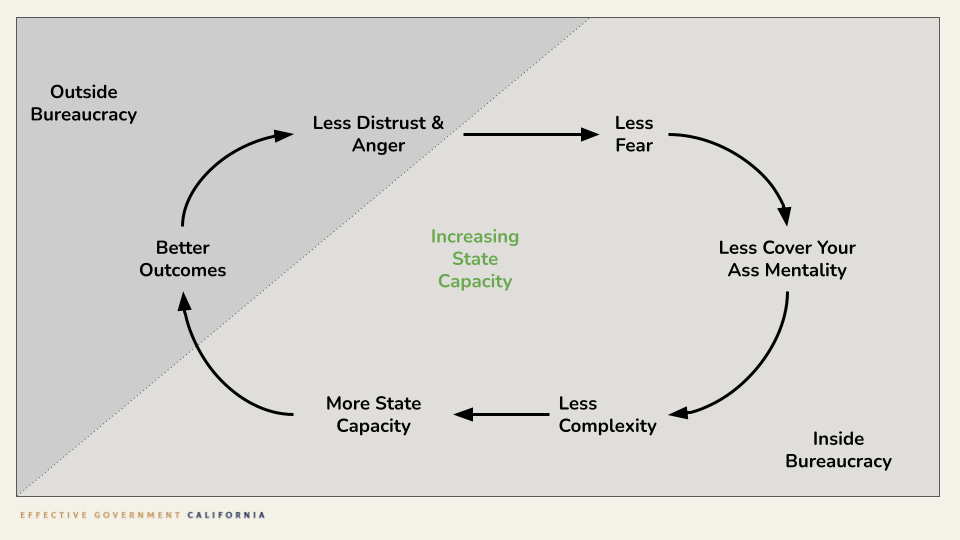

According to government reformer Ken Miller, complexity is why we lack state capacity. And the root cause of complexity is a “cover your ass” (CYA) mentality. And the root cause of CYA is fear.

The only long term way to fend off bureaucracy is to drive out fear.2 Any attempt to attack government or “hold government accountable” — especially from the outside — just increases fear, which drives worse outcomes.

Reversing this is generational, cultural work.

We need to recommit to believing government can be good and do good. “We are the government; the government is us, you and I,” per Teddy Roosevelt.

We need to elevate the spirit of JFK and bury Reagan. Working for government must be noble and cool again.3

If we do that, we can kick off a virtuous loop running in the other direction:

But reimagining government will likely require pushing for politically unpopular changes. Over the past decades we’ve implemented a bunch of controls that seem common sense on the surface but are rooted in distrust: we want government hiring to be fair so encumber the process with a thicket of rules; we want lots of independently elected officials so no one player in the system gains too much power; we want many points for citizen input to ensure all communities are represented in decision-making; we want transparency in government to prevent graft.

Each idea above, and countless others, sound reasonable. But they add up to a dysfunctional system.

Building a new system and taking on the interests invested in the industrial-era status quo requires an attractive vision where regular voters can see themselves better off.

Doing good government for good government’s sake — state capacity for state capacity’s sake — will not get us there. Lots of smart people have spent lots of money over the past couple decades on “reinventing government” efforts, and they’ve largely been unsuccessful.

Instead, the path forward is to take the ideas in state capacity and yoke them to the current political energy4 around issues like housing and climate. We need to fuse State Capacity & Abundance.

We didn’t have state capacity in the post-WWII era for the sake of it. We had it because we were tackling an aspirational (or existential) mission of defeating the Russians, sending a man to the moon, and building the American Dream. And in turn we were able to achieve those things because we had state capacity.

What Might Modern State Capacity / 21st Century Government Look Like?

What might modern government look like? The North Star is an adaptive organization that’s set up for continuous learning and improvement. That means things like having feedback loops to enable continuous learning, everything from embedding RCTs in programs to studying positive deviance to constant cohorting & networking of staff who run California’s 482 cities, 58 counties, 1000+ school districts, and 3,000+ water & fire districts.

We also need government to be a place where great people can do their best work, on behalf of their fellow citizens. That means reversing the cultural denigration of government as an institution, creating more autonomy for government staff to drive outcomes, making sure pay is somewhat competitive with the private sector5, and a laundry list of other improvements. We need to shift the image and expectation of government staff from Parks & Rec style bumbling to Starfleet level excellence.

All this will take resources — we are woefully shortsighted not to invest them. Government is over 35% of GDP — what % should we set aside to make it a continuously improving system? While we flow lots of money through government, we don’t actually invest substantially in training, collaboration, tools, etc.6

We also don’t have the mechanic or culture of centering the user. Instead we center the bureaucracy. Implementers don’t talk to end users enough in the design of our systems — because they’re overstretched implementing flawed policy — and legislators don’t talk to implementers (and end users) enough to know how they’ll actually use their “product” (policy) because they’re understaffed in terms of human capital. At the municipal level, services are still vertically siloed, instead of meeting the user where they are.

Our benefits system is tragically fragmented, forcing Californians to jump through tons of hoops and disparate forms to receive earned income tax credits, Calfresh food benefits, public transit assistance and many other benefits. This lack of user-centeredness is mirrored in the tangled thicket of jurisdictions and rules that civil servants must navigate to address basic public needs like ensuring a reliable supply of clean drinking water.7

To countervail our status quo bias, we need to look at the costs of inaction vs. action.8 The “compared to what” framework forces us investigate the harms of the status quo vs. just pointing out flaws in the new thing. We live in a golden era of empirical social sciences, with digital tools providing radically better computation and access to critical data. Our ability to measure the counterfactual of doing nothing versus a proposed alternative has never been better, but still we are stuck in an obsolete waterfall mode of developing, implementing and evaluating public action.

In a more trusting, less fearful environment, data can be a compass for continuous improvement instead of a scorecard for meting out punishment and “accountability.”

What Comes Next?

So where do we go from here. First and foremost we have community-knitting and identity-building to do. It’s only when an identity emerges that the flywheel will really start spinning; donors donating; candidates running; advocates advocating; talent accumulating; all networked together, and working towards an aspirational vision and a common purpose bigger than any one narrow effort.

Important sub-communities already exist: on the Abundance policy side, there are the YIMBYs, a YIMBY-oriented subset of climate activists, public spaces & safe streets & bike/walk activists, and potentially wings of many more groups like CJR, homeless advocates, etc.

On the state capacity side, there are countless public servants working quietly within government to improve their corner of the much larger system. There are also the civic tech groups (e.g. Code For America, US Digital Service, 18F), government performance folks (e.g. Bloomberg Philanthropies, Government Performance Lab, Results for America) and other lean and process people (e.g. Ken Miller). Some of these groups have been funded to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars. But they’re still not political forces.

As a state legislator recently told us: Political power is generated when a group of people — sometimes a small group — work together in lock step.9

The original Progressive Movement of the early 20th century was a multi-decade fight to update our Agrarian-era government to fit the Industrial Age. The Progressive platform aimed to achieve inspiring public policy goals via updating the operations of government (e.g. civil service, municipal budgeting).

If the Abundance Movement is to succeed in moving us from Industrial-era to Knowledge-era government, we’ll again need to fuse it with an effort to actually revamp how government works. We should see Abundance & State Capacity as twin flames, and internalize how both efforts need one another to succeed.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Thanks to all the folks who shaped this piece: Annie Fryman, Brink Lindsey, Jen Pahlka, Joe Ensminger, Ken Miller, Kris Balderston, Lenny Mendonca, Monica Chellam, Patrick Atwater, Steve Goldsmith, and Zack Rosen.

In startup terms, Abundance = a strong, coherent product vision; State capacity = an engineering/product team who can ship great features.

Trust issues are not unique to government; they seem to naturally arise in any large bureaucracy as an outgrowth of the principal-agent problem.

While researching this post we talked to a senior government official. He had a poster of JFK in his office. He said he was 5 years old when he decided to work in public service, because he idolized JFK. There are a generation of folks who went into government because going into government was a cool and noble thing to do. After Reagan made government the enemy, that pipeline shrank.

There is also a compelling “Why Now?” for this reform movement. The blunt reality is governmental failures over the past few decades have had limited effects on the upper ~third of society. Yes, certain systems — e.g. child welfare, mental health, criminal justice, public education — weren’t getting great outcomes. But as a wealthier person in society, you had relatively little interaction with these systems, and to the extent you did, you could opt out into private systems. It’s not nearly as easy to opt out of our coming challenges — democratic backsliding, climate change, wildfires, homelessness & public safety, even nuclear war. In labor parlance, this can spark a shift from “exit” to “voice.”

As one among many examples, we’ve constrained the budgets of CA legislative offices such that they can only afford to pay much of their staff ~$40,000-50,000, which gets them ambitious staffers a year or two out of undergrad. These young people work hard, but are ultimately inexperienced and under-qualified to stand up against the veteran lobbyists they spar with during the legislative process.

Putting together rigorous estimates are beyond the scope of this article. But much of the professional development activities happen via industry associations like League of Cities, CSAC (counties), ACWA (water). We estimate these efforts are on the order of tens of millions of dollars per year. As a % of our $300 billion CA budget, these are minuscule investments in state capacity.

For example, stormwater management is fragmented across cities that plan and permit land use decisions, water retailers with an interest in that scarce water, wastewater entities with responsibilities for cleaning up the runoff and public works that maintains streets and other hardscape. Those often are not just different departments but entirely different organizations in the same geographic area. Novel sensing technologies and smarter green infrastructure practices exist and have been proven to capture more stormwater but struggle to breakthrough bureaucratic inertia. Meanwhile, rain falls where it may, regardless of the lines we draw on a map or boxes on org charts.

As Frank Baumgartner and Marie Hojnacki’s “Lobbying and Policy Change: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why” points out, the status quo almost always wins. H/t to Matt Yglesias for surfacing this insight in a recent Slow Boring piece.

Political power is also a function of macro conditions. In this case, one factor putting wind at the back of the Abundance community is ~$100 billion in new California infrastructure funding from the state & federal government. This can be a catalyst to regain our capacity to build.

"We also don’t have the mechanic or culture of centering the user. Instead we center the bureaucracy. Implementers don’t talk to end users enough in the design of our systems — because they’re overstretched implementing flawed policy — and legislators don’t talk to implementers (and end users) enough to know how they’ll actually use their “product” (policy) because they’re understaffed in terms of human capital."

This is such an important point. My day job is tech support, so I am very familiar with the idea of managing and passing around tickets, and having managers whose whole job it is to track our service quality -- how long do we take to answer our customers' requests, how many contacts does it take before we solve their problems, what is customer sentiment through the process.

We seriously need to get our government organizations to adopt this kind of CRM system, and to understand that "customer satisfaction" is critical to maintaining legitimacy and social cohesion. If the general public comes to feel the government doesn't listen to or care about them, it's very hard to maintain a democracy.

Everything from the DMV, to the IRS, to your local building department, needs both technical investment, and adequate staffing, so that people feel like their interactions with government run smoothly and treat them fairly.

You have a lovely vision. You reference the Progressive movement of 100+ years ago, but you don't seem to recognize that most of the things you advocate were also things the Progressives advocated.

The problems you've identified with government action were natural results of the Progressive reforms - inevitable, even. I don't disparage the Progressives or their reforms - they addressed real problems of the spoils system and politics controlled by party hacks, of a scale that's hard for people of our era to imagine. Their solutions (civil service; detailed procedures for inspection, procurement, and approvals; local control of land use, etc.) are what have led to the current problems you identify.

You blame Ronald Reagan for turning people against the government, but you have the causation backward. Ronald Reagan was elected president because most voters had lost faith in the liberal vision of government; voters didn't turn against government because of Ronald Regan's rhetorical powers.

You seem to rely on increased government capacity to solve all the hard problems society faces. I think this is profoundly mistaken. If you could build a new government from the ground up, based on your vision of the ideal society and effective government (after convincing your fellow citizens), and if you could select government officials and workers to faithfully implement your vision, you might have success. However, anything you can build will be built atop the governments we already have, mostly under the rules we already have, with the workers and officials we already have, with organizational cultures that are the heart of the problems you identify.

If you want to make progress, pick one area, and lay out a plausible solution. If I were a Californian, I'd probably start with housing. I'd identify the problems as mostly coming from obstacles to building more housing, and more affordable housing. These obstacles come from excessive local control that is used to keep poor and working class (and even middle class) people out of "desirable" towns and neighborhoods. Rather than try to push new housing plans through current governing bodies and permitting procedures, I'd work to weaken (or destroy) the bodies: abolish the Coastal Commission, limit the power of zoning boards, with a strong bias towards rights of owners to use their land as they see fit.

Or, pick "Clean energy". You don't spell out your vision of clean energy, but most self-identified progressives take zero net emissions as a fundamental requirement. There is currently no path to achieve this goal while maintaining what we would recognize as a modern lifestyle. There is no way to deliver reliable electricity 24 hours per day without significant reliance on fossil fuels. (Technically, we could probably achieve reliable zero-emissions electricity with heavy reliance on nuclear power, but there doesn't seem to be any constituency working for this.) There is no path to maintaining significant long-distance transportation without the use of fossil fuels. There is no path to producing significant metal products without the use of fossil fuels. If you want to achieve anything in this area, you need to work with people who understand these areas, and start with some realistic goals. Then, try to convince your fellow citizens that the goals are worth pursuing at the costs that would be required. California's (and the US's) current approach is to impose mandates without regard to feasibility, and spend as much money as politically feasible, without regard to actual effectiveness.